The Wind Will Carry Us

On Iran and Fantastic Landscapes for our Imagination to land on.

I used to watch quite a bit of cinema in my youth; over time, with the progression of life, the habit fell by the wayside. My 2022 resolution is to get back into watching more cinema, you know like real cinema, not YOU Season 3. I watched my first Kiarostami film on Mubi yesterday - The Wind Will Carry Us (1999). It took me a while to get used to the slow pace of the film, forgive my Netflix-watching internal rhythms.

The film focuses around an urbane engineer who comes to a village, to attend to an ailing relative, and has a bit of an adventure. I won’t give away more of the not-really-a-plot, in case you want to watch the movie yourself. The engineer makes friends with a rather precocious and endearing kid. In some ways, Kiarostami’s story- telling technique strung by the conversations between the man and the boy reminded me of Ray’s handling of the little boy, Apu, in Pather Panchali. The boy is crucial to the story, almost as a translator of the village to this urban man.

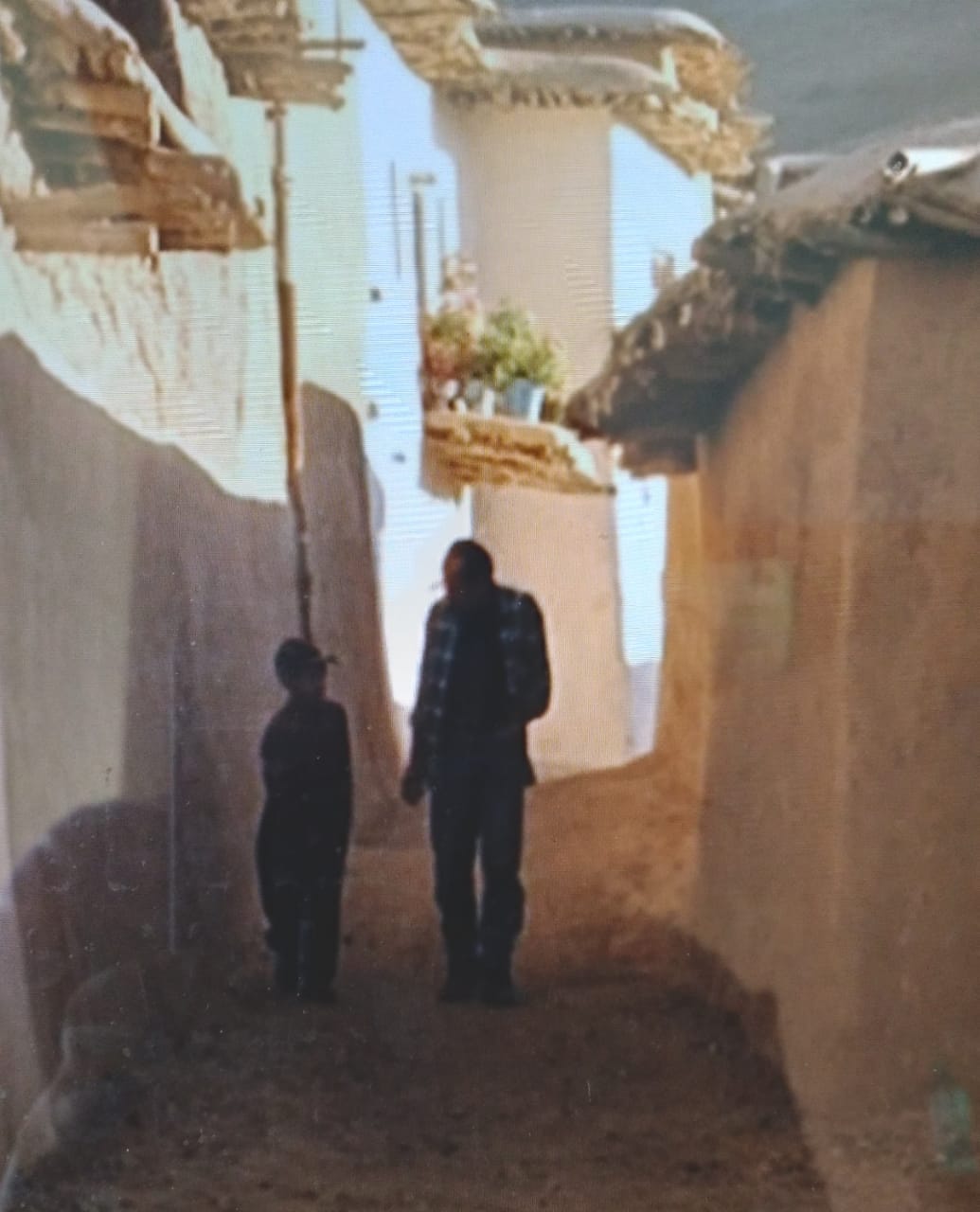

Frankly, I realized within 45 minutes of the film that other than a human bone being excavated by a local archaeological site, not much else was going to happen in the film. But I want to dwell upon the montage of landscapes from rural Iran that Kiarostami’s frames so lovingly embrace. Each frame of the open fields, the first shot of the car maneuvering through the winding mountainous road, the boy and the man walking through the stony paths of the village, the women going about their daily scores - exceeds language in a way that I am reminded only film or art can accomplish.

There is another character in the film - a 90s-style, humongous mobile phone with an antenna sticking out. One that can deliver voice and sound only at a considerable altitude. The engineer consciously carries it around in his pocket, for it has been taken on hire. It is the awkward cellphone that reminds us that we are, even in the film, within the fold of recognisable time. Rurality, like in Ray’s Pather Panchali, a recurrent filmic route to escape. It is beautiful, full of pathos, and out of time. And in Kiarostami’s pallette, the cellphone rings to remind us that an engineer has travelled in a beat-up car to take in this mythical timelessness. Kiarostami’s film is a pointless poem; critics say it is a celebration of the human spirit. I don’t know about that. It certainly quenches the thirst of the eye, the eye that has been immersed in the visual field of the junkyard of spy-thrillers and urban-love-triangles for so long.