Inwardness

Early notes on my learnings from Buddhist teachers

I am new to the study and practice of Buddhism, so these are naive, early notes. While experimenting with some forms of meditation taught by Buddhist teachers, I became more and more aware of (albeit, somewhat irritated by) my writing life. I turn everything into writing, and often, without processing thoroughly the expereince itself. Eveything becomes an attempt to tell the world about the world washing over me in purple prose. But it is perhaps also a way lead the contemplative (if slightly, aloof and vain) life.

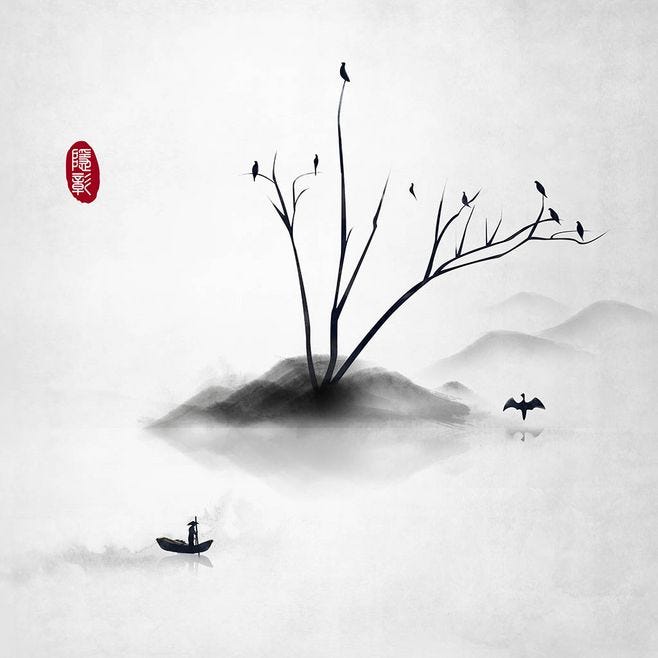

[Chinese ink wash painting. Source: https://www.chinaartlover.com/what-is-chinese-ink-wash-painting-or-shui-mo-hua-%E6%B0%B4%E5%A2%A8%E7%95%AB]

I began thinking about attention through Jonardon Ganeri’s work on attention, inwardness, interiority, and the question of inside/outside divides. In his 2021 book Inwardness: An Outsider’s Guide, he discusses disparate diagnoses on attention - from St. Augustine to Borges, Fernando Pessoa, Simone Weil. Each of his interlocutors give a different account of what makes us believe that something exists in the world out there, until we cast our attention on it, and are fixed by it. How to recognise, modulate and use powers of perception and attention form a good part of mind-body practices in Buddhism and Hinduism, maybe in other religions too. These are not simply stress-busters, or hacks for greater productivity, but invitations to take on the mysteries of being. These are primarily protocols of mental discipline, quite separate from the coercive hacks of pomodoro that we resort to, in order to have some quiet in our minds in the condition of turbulent modernity that we find ourselves in.

Ganeri begins with advice given by a Buddhist monk to the protagonist in a Sanskrit play writtten by Asvaghosa:

the careful examiners who know interiority are doctors for minds filled with passion and dark ignorance.

I am not so averse to ‘passion and dark ignorance’ - I think those are productive forces too. To look inward is often a journey we undertake in psychotherapy or psychoanalysis, the latter being one that takes the ‘patient’ closer to their hidden, buried subconconscious - a kind of archaeology of the self. What we find in these practices, is often, the legibility and illumination of hidden patterns of learnt behaviour which have their roots in past (often, childhood) experiences, and some practical elements - often called triggers - in the outside world which provoke in us reactions that are learnt from our past experience and conditioning. This interiority, as I am learning from reading Ganeri, and from Buddhist meditation teachers like Joseph Goldstein, is only a route to our thought patterns. These practices may not necessarily lead us beyond. The interior, if at all, there is such a thing as a discrete entity, can be experienced in meditation by exercising some kind of extreme attention. Attention that makes alive to the absolute split-second here and now, attention on the clock ticking, bird chirping, skin wrinkling, insect burrowing, snowflake settling, all the things that are caught in the motor of perception but are relegated to background noise because we are caught up in an endless cycle of thought.

As an ethnographer, I am begininnng to ask if there is something to learn from this corpus of texts and practical work protocols, that can inform our research method of ethnography. Ethnography is often described in terms of narrative and empathetic attention. Can we exercise waking attention of an extreme and mindful variety in our fieldwork as an ethnographic protocol? I will find out as I continue my ethnographic research of everyday life of devotion in the Bhakti tradition in northern India, later this year. I wish to continue my attempts at sitting and walking meditation while immersing in the lifeworld of Vrindavan. Let’s see what happens to the ethnographic protocol thereafter, and if I am able to access a trained, careful interior through my practice.

[If this is of any use, I am using Sam Harris’s Buddhist meditation app Waking Up - a very helpful aid, as I am finding out, for slowly learning this practice and the wisdom behind it.]