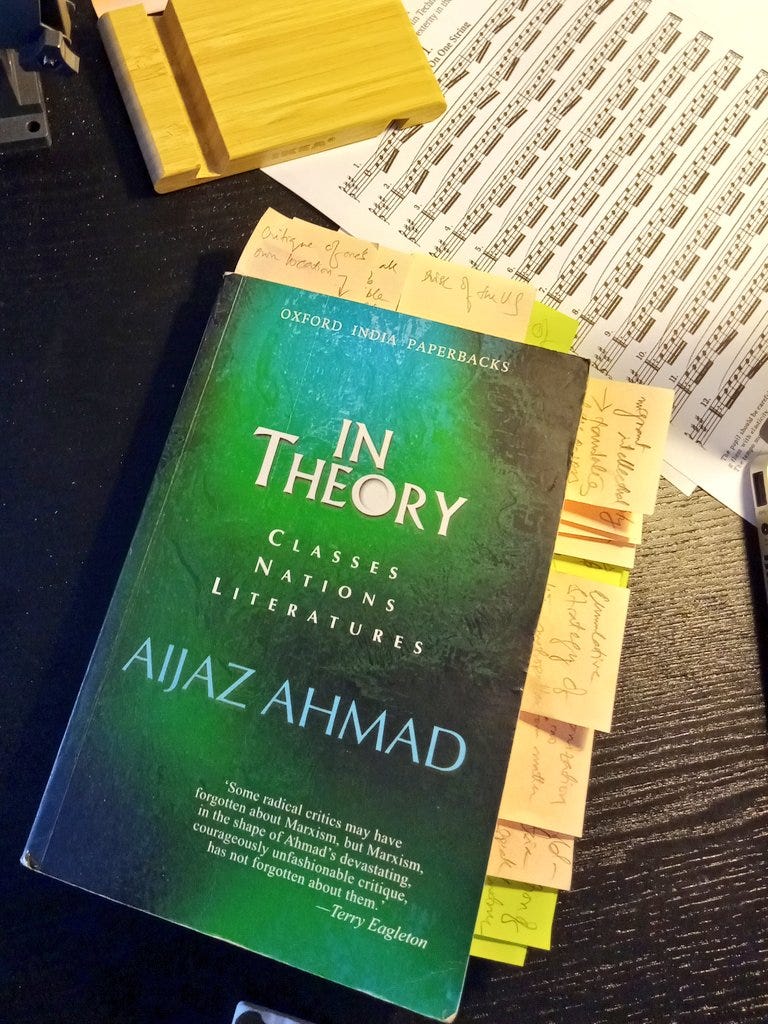

In Theory

A bit text from our new podcast The Big Book Project

Aijaz Ahmad, in the provocative collection of essays In Theory: Classes, Nations, Literartures (1992) situates the category of the Third World in a longish historical analysis of the Non-Aligned Movement, the Bandung Conference of 1955, and so on. But throughout the book, Ahmad’s purpose is to critically treat this category and its rise and spread, (Ahmad, we must remember is writing in the 1980s and early 1990s) and its gain of much facility and cache in the quarters of literary theory and criticism. The Third World, in this sense, is a geography outside the battlefield of the First and the Second Worlds - the two purported protagonists of the lengthy Cold War. The Third World also emerges a discursive field of talking about all these other political and cultural formations that come to the fore through the decolonizing moment of the mid-twentieth century. These are amorphous peoples of unspeakable vastness in terms of number and diversity, their reality though is coined pithily in that one formulation - the Third World.

Ahmad intervenes in this discourse to point out the fatal flaw. This flaw lies in showing (mostly Anglophone) literatures coming out of Third World, that find some circulation in the Western public sphere - famously, names like Rushdie and Marquez and Achebe - as national allegories of the composite and complex set of experiences of people living in these nations, and nation-states, that these authors have origins in. Why a work of literary flair should be considered an allegory for the national space and time in the Third World, it is not clear, Ahmad points out, while the same rule is not applied to uncover the nature of experience of the collective (nationally or regionally speaking) in the First World (or the Second World) through the voice of one literary work that originates in that area. This is the fulcrum of the theoretical violence done by some quarters of Western Marxism as well as postmodern circles in western universities that take Rushdie to be a signature of South Asia, but would refrain from taking Dickens to be a symptom of England or Emily Dickinson to be a symptom of America. Ahmad’s battle with western Marxist theory (of some descriptions) is executed best through his critique of Jameson, and his lengthy chapter on Edward Said, though I find the criticism of the rising literary figure of the late 1980s, a young Salman Rushdie, a bit tenuous.

Let me explain how I see Ahmad’s Marxism. He refuses to reduce literature or culture as symptomatic of material, worldly conditions of a people. Moreover, he refuses to see national elites as spokespersons of the material, affective or political milieux of nation-states in the Third World. This is where his hard-hitting class analysis lies. Ahmad calls out people who translate their non-western origins as social capital to gain entry into halls of privilege in the West, including western universities, often making exaggerated (even falalcious) representations about the nature of life and aspirational horizons of large numbers from the regions and nations they come from. The West wrongly interpellates their ‘difference’ as representative of their national/regional condition that their biographies originate in. So one (myself included) becomes a South Asianist scholar, or an Africanist literary theorist or some such. This neat representative infrastructure generates a grade of elite opportunism within the West and located in the Third World. It permeates deeply into diversity politics as practised in the liberal environs of the western university and beyond. The other important strand of Ahmad’s Literary Marxism lies in his steadfast refusal to see the individual fictional work as representative of the ‘tale of the tribe’ (to use his own words). Literature has a curious representative function of the society and time from which it grows, but it manages to accomplish much beyond acting a socio-cultural biography. Neither Dickens’ nor Joyce’s works would ever be read as a state-of-England or state-of-Ireland novels. There is no reason why Indian or Ghanaian or Indonesian ones should be read thus. In light of these early notes, go check out our podcast The Big Book Project.